| INDEX | 1300-1599 | 1600s | 1700s | 1800s | 1900s | CROSS-ERA | ETHNO | |

| MISCELLANY | CONTACT | SEARCH | |

As this site is divided into eras, technical hints tend to be scattered all across. Most of them are found in the 18th and early 20th century chapters – the latter are also relevant for the late 19th century, and there you have it: Not all techniques are restricted to one era. This page contains some cross-era hints.

Patterns on this site, and many from books, have to be scaled up from a printable to a usable size. There's an extra page for that.

Then you have to fit the pattern to your size. There's a loot of books

that deal with this problem. They are meant for modern patterns, but the priciple

is the same. With the usually close-fitting bodices, you should always make

a mock-up out of cheap fabric, anyway. Fit it over the underwear that was normally

used during the period you have in mind, e.g. shift, stays and paniers or shift,

corset and bustle. Wear the mock-up with the seam allowances facing outwards

for easier adjustments. If possible at all, the fitting should be done by someone

who knows a thing or two about sewing and fitting. If you don't have such a

someone available, a dummy will have to do, but consider that modern dummies

don't have the shape of a corseted body - even if you put your corset on it.

In the 18th century, for instance, the stays pushed the breasts up, but try

that with a modern dummy... I haven't tried that yet, but maybe it works if

you use a smaller dummy, put your corset on it, and stuff rags into it wherever

needed.

If seam lines need to be altered, have them marked on the mock-up fabric, not

just pinned. Take the mock-up apart, cut it along the new lines, and either

use these pieces of fabric as pattern or copy the changes back onto paper.

are an unusual sight for anyone used to modern sewing techniques. Teachers and books have done their worst to persuade us that they are hideous. However, this demonisation of visible seams was invented only in the latter half of the 19th century. Before that, seamstresses had a much more relaxed view. For instance, darts that were introduced during fitting can be folded down onto the fabric and affixed there with running stitches along the edge – only by hand, of course, and with small and regular stitches. For the late 19th century and later, I'm afraid you will have to turn the darts around to the back and sew them from there.You'll have to be very careful when doing so lest they slip.

Somewhere between 1800 and 1810 (I don't remember the exact year, but the number '1806' is jumping up and down and waving at the back of my mind) a technique was invented that allowed the production of cotton thread strong enough for sewing. Before that, only linen and silk thread were tearproof enough to be used as sewing thread. Silk thread was too precious to use on linen and wool fabrics, so silk was sewn with silk thread, linen and wool with linen thread. Before the invention of chemical dyes (late 19th century), linen was difficult to dye, so most linen sewing thread was usually left undyed. It is, therefore, perfectly authentic to use unbleached linen thread on, e.g., dark blue wool fabric. If you take authenticity far enough to use undyed thread, you should always sew the seams by hand: If the seam is pulled apart under strain, a machine seam would be too conspicuous.

is, to some extent, part of the "visible seam" theme. When fabrics were woven by hand, they usually were only 60-80 cm wide and more expensive than the labour that went into tailoring. Making the most of the fabric available was an art in itself. You may have experienced cases where economical use ofthe fabric wasn't possible just because of a tiny corner of the pattern piece didn't fit onto the fabric. Nowadays, you move the piece until it fits, even if it means that you need half a metre more. In earlier times, one would have thought nothing of cutting the missing corner from some other part of the fabric – even if the seam where it was sewn on was visible, even if the missing corner was only the size of a thumbnail. I've even seen an extant dress where the compère – a highly visible part of the dress – was pieced together out of ten or more pieces without any regard for the (striped!) pattern.

My Mom taught me to neaten edges by going along them with zig-zag stitches (machined, of course). Not a very period technique. The modern obsession with neatening is, just like invisible seams, a heritage of the somewhat anal-retentive late 19th century. For any pre-1800s costume, it is perfectly fine if you leave edges un-neatened, unless the fabric has a strong tendency to fray. Even then, a wide enough allowance usually takes care of the fraying. In case of ruffles, even visible edges were left un-neatened and were pinked instead. The edges of felted wool fabrics were often not turned under, but stayed visible even on upperclass garments. This is especially welcome for cloaks, whose rounded eges are not easy to turn.

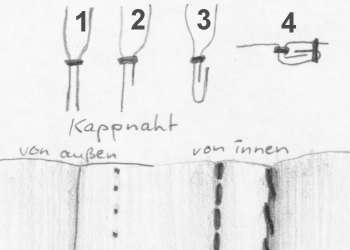

The late 19th century takes a completely different view: Fabric edges had to be neatened at least with whipping stitches, but preferably with bias tape, and possibly affix them to the top fabric as well to make sure they lay flat. The advent of the sewing machine may have played a role there: Sewing straight seams had become so easy that it wasn't a status symbol anymore, so neatened seams (which had to be done by hand) became a mark of upperclass garments.

Nowadays, the main purpose of lining is to prevent fabric layers from sticking to each other by friction. Modern lining, therefore, has to be smooth and lightweight. Until the early 20th century, however, the main purpose of lining was to hold the garment together and in shape. Often (especially bodices of women's garments) the lining would be modeled onto the corseted body and the top fabric mounted onto it. If one removed the lining, the garment would collapse in a heap like a body without a skeleton. Therefore, lining fabrics usually were relatively stiff and strong up until about 1910, or at least doubled with a stiff interlining.

During the 19th century, lining and top fabric were often treated as one, i.e. they were placed on top of each other and then sewn up together. The advantage of this technique is that the lining can support the top fabric better. Disadvantage: The fabric edges stays visible that way, so they have to be neatened extra. Maybe that's one of the reasons why the 19th century was so obsessed with neatening. Skirts, too were lined full length and width and the layers treated as one. It requires very careful smoothing-out and basting to make sure that the layers don't bag. More about late 19th/early 20th century techniques can be found here.

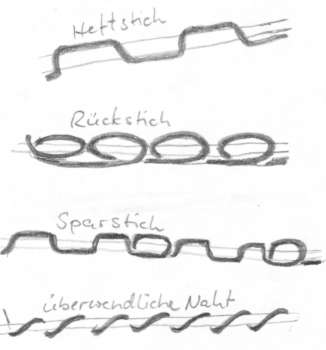

is so unfamiliar to most people nowadays that they have to learn it from scratch. My mother actually firmly believes that hand seams are weaker than machine seams, in spite of all my garments that prove otherwise. Unpicking a machine seam is much easier than unpicking a hand seam. Have you ever had a button fall off a store-bought garment? That wouldn't have happened if it had been sewn on by hand.

Another common reaction is "Oh dear, I'd never get anything finished that way!" Well, if you're not a purist (and a purist would never react that way), you can sew hidden seams with the machine. But that's not the point. My point is: Try to get rid of all the prejudices you may have and simply try it! The stitches don't have to be as small and regular as the machine makes them. Of course small and regular stitches were always prized as signs of good quality, but to a certain extent, the machine has pampered our eyes too much. Maybe you have cursed when sewing something complicated like a modern revers? Try sewing such things by hand. It's usually quicker than machining, noticing that you've made a mistake, removing the seam, trying again...

As with all things, practice makes perfect. Many people I've met sewed an inch or two, then threw down the workpiece and stated that they simply didn't have the talent. That's a popular method with lazy people and especially with men who hope that some woman will take heart and do it for them. What they don't consider is that sewing is a lot easier than, say, reading or driving, but most people manage and would be quite offended if somebody suspected them of not being able to. They forget that reasing and driving, too, didn't come easily at first try.

For a strong, handsome hand seam, the stitches shouldn't be longer than 3 mm; in case of thicker woolens sewn with linen thread, 4-5 mm are OK. The thinner the fabic, the thinner the thread should be, and the shorter the stitches. Otherwise the seam becomes too loose, thus supporing the prejudice about hand seams not being strong enough. Remember to pull the thread tight with each stitch.

I am well aware that these descriptions may not be clear enough. As is so often the case with sewing, it's best if you find someone to show you how it's done. Any good tailoring book, especially those published before 1960, should also be of help.

Wednesday, 24-Apr-2013 21:47:22 CEST

Content, layout and images of this page

and any sub-page of the domains marquise.de, contouche.de, lumieres.de, manteau.de and costumebase.org are copyright (c) 1997-2022 by Alexa Bender. All rights reserved. See Copyright Page. GDPO

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.