| INDEX | 1300-1599 | 1600s | 1700s | 1800s | 1900s | CROSS-ERA | ETHNO | |

| MISCELLANY | CONTACT | SEARCH | |

|

|

There seem to be very few extant examples. The Musée Galliera in Paris owns a court bodice worn by Marie Antoinette. The Livrustkammaren in Stockholm have, among others, the full coronation robe of Luise Ulrike (aka Lovisa Ulrika) of Prussia. The chances are slim of obtaining permission to study them. Moreover, these two examples are clearly court dress. So we are, in the main, reduced to looking at paintings as closely as possible.

Some questions that arise are

ad 1) The fact that some dresses have clearly visible waist tabs indicates that the two are separate, the bodice being made up very much like a pair of stays. That leaves the question of how the skirt is worn: All of it underneath the bodice, or underneath the tip in front and on top of the tabs at the sides and in back, as was the case in the 17th century? Dresses without tabs look as if the skirt went under the bodice - it might be sewn to the bodice from the inside.

ad 2) As the front is closed, the most probable answer is: Down the centre back. As hooks & eyes were not terribly popular at the time, it was probably laced. Both would be in keeping with earlier, 17th century styles of similar appearance.

ad 3) I know of only two pictures that show the dresses from the back. One is Nilson's Minuet you have seen on the Allemande cover page, the other a rather small detail from a larger painting. In both cases, the waistline in back is pointed without tabs showing. So the skirt can't be worn on top of the bodice in back - it must be either worn completely underneath, or on top of the tabs only at the sides. But if that is the case, and the waistline smooth (without tabs), then the bodice can't have tabs except maybe at the sides, or else they would be visible.

ad 4) The overall stiffness of the appearance suggests that boning must enter into it at some point. The question is whether the boning is in the bodice. In some paintings it is possible to discern slight, straight shadows that may or may not be boning showing through. However, the question can not be satisfactorily answered by the mere study of paintings.

ad 5) Very probably, yes. If you look closely at the painting of Therese Kunigunde of Bavaria, you will notice an edge of shadow running straight from the neckline to the armpit. It looks suspiciously like the edge of stays underneath. Both the slit-front and the wrapped-front variations would require quite inventive boning techniques if they were to be sufficiently boned to replace the stays and look loosely draped.

A friend of mine has had the rare luck of finding an extant bodice and skirt in the vaults of a small town museum. With her help, I was able to examine it closely.

It is only lightly boned, so it was probably worn over stays. The wearer must have been smallish, but wide-chested.

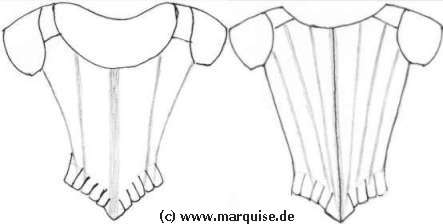

There is one front part, two side parts and four back parts plus the sleeves and shoulder parts, made up of a simple white fabric which could be linen or calico. The top fabric is cloth of silver, the front being made up of three parts (whereas the foundation is in one piece), the middle one cut to fold. Apart from that, the construction is the same as for a corset: Lacing holes at alternating heights neatened with whip stitches, bound tabs down from the waistline, a cord to mark the waistline. So that answers the question of how the bodice was closed.

The second picture illustrates the placement of the boning. As usual with corsets as well, they are placed between the layers of the foundation fabric. There is one bone each to either side of the opening, and another on the other side of the holes (not shown here). The others follow the back and side seams. The centre front is held straight by a much wider strip of whalebone, but not a proper busk. Apart from that, there are only two bones in the front part, running pretty much parallel to the centre front.

What comes as a surprise is that the back has more bones than the front, while with stays it's usually the other way round - and for good reason, as the fashionable breast shape could only be attained by strong boning. I believe the reason to be that in back there are many seams which would obscure the outline of the bones, while in the smooth front they would show through the fabric. As the measurements suggest that the original owner was rather wide-chested, she must have worn stays underneath.

She very short sleeves as well as the decorated tabs and the rich fabric suggest that this bodice was meant to mimick French court style.

The skirt has also survived, but it was taken off the waistband at some time, so we can't tell exactly what shape it had. We can't even be sure that it wasn't attached to the bodice, although it seems improbable. If it was, one would expect pin holes on the inside of the bodice, but there aren't any. What is left is a long rectangle with two slits on either side of the (lengthwise) middle. I didn't measure the slits, but from memory, I'd say they were 20-25 cm long. We'd wondered what they were there for. My theory is that the rectangular flap between them and longish triangles on their outsides were folded down, thus forming a dip in the waistline that was necessary to even out the front length of the skirt and the side length, which had to be longer over the panier.

This garment has never been dated by anyone halfway knowledgeable in costume history, and the provenance not properly recorded. Apparently, it belonged to a family of the lesser nobility in Thuringia.

Next chapter: Was it really so widely used in Germany?

Content, layout and images of this page

and any sub-page of the domains marquise.de, contouche.de, lumieres.de, manteau.de and costumebase.org are copyright (c) 1997-2022 by Alexa Bender. All rights reserved. See Copyright Page. GDPO

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons License.